No, seriously.

Ok, here goes:

And by thing I mean papers.

There, I’ve said it.

But seriously, I do. They do nothing for me that can’t be accomplished through better means. I mostly teach introduction to sociology here, so, my main goal is to make students understand what sociology is, how to apply its core concepts and ideas to, well, everything, and what it is means to think sociologically. Traditional papers and assignments don’t accomplish much of that, in my not-so-humble opinion.

First, most traditional intro to sociology assignments are already online, ready to be plagiarized with a simple Google search (not to mention Course Hero, Chegg, and other such places).

Second, students have written papers for years and they have learned how to fill up pages and pages with what I call bloatware: text that says nothing or close to nothing, but fills up pages until they hit the assigned word / page count. I’ll be lucky if papers have paragraphs. They have also have learned to use their writing to obfuscate and hide what they don’t know.

So, no more papers. Ever.

What else then? Well, I have largely used non-traditional assignments both in content and format. And yes, I have made extensive use of mind maps for a variety of tasks. Maps are, frankly, one of the best ways of representing content that I can think of.

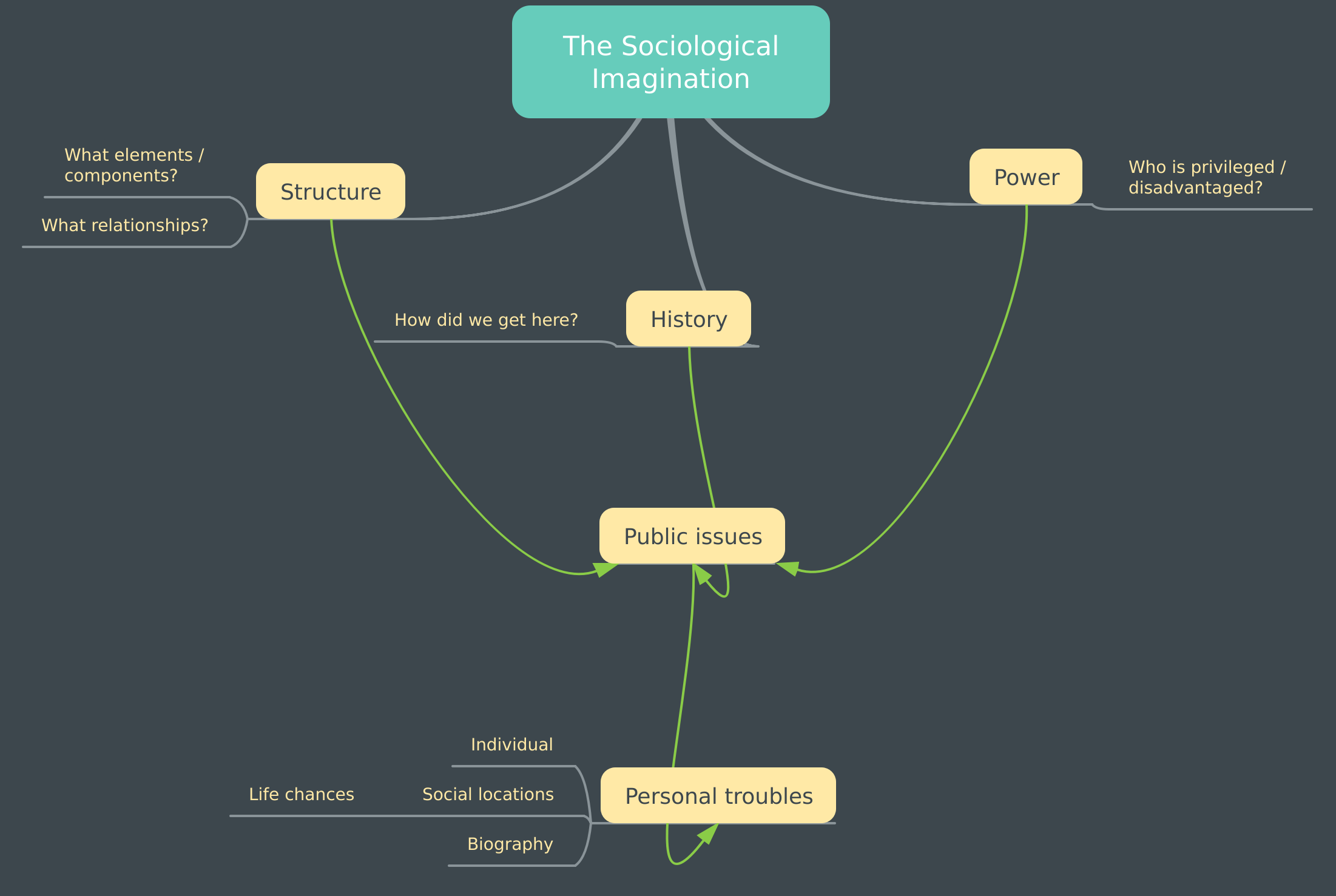

So what is mapping, exactly? As the name indicates, it is a visual way of representing content that especially emphasizes hierarchy, order, and connections. Mapping is especially useful when one is dealing with content that is non-linear but has multiple elements that are connected in different ways. This is a first benefit over papers, which, unless you use hypertext, are linear by definition.

For instance, here is a simple map of the concept of sociological imagination broken up into its basic components and their relationships:

So, if we are interested in representing complex situations (as is pretty much always the case in the social sciences), where elements are connected together in a variety of ways, but not of equal important or influence, mapping is a lot more useful than just writing papers. At the same time, mapping allows us to have both a larger view of an entire situation or problem, and to dive into the different components of the map for details. Maps are flexible, they can take any number of formats, with as little or as much detail as needed. There is no single good way to map, so, even with the same instructions, one is likely to have to grade 35 times the same work and then this happens to you:

I should note, right away, that I am not a purist, so I tend to use mind maps, concept maps, flow charts, and process maps pretty much interchangeably because they all boil down to visually representing phenomena, situations, problems, etc, in a way that captures importance, hierarchy, and connections.

If you are familiar with the literature on the scholarship of teaching and learning (sotl), mind maps are mentioned all the time, so, I am not being completely crazy here.

How do I use maps ? In this post, I’ll discuss mapping chapter outlines. In the next one, I’ll discuss mapping actual content.

Mapping chapter outlines

As I tell my students, say, you were asked to drive from your home to a destination to which you’ve never been before, would you just get into your car and just start driving until you ran out of gas? Probably not. And yet, when our students read their textbooks, that is pretty much what they do. They start reading until either some more fun distraction happens (a text, a social media notification, anything), or they get bored to tears, because, let’s face it, textbooks are not a fun read. If they are diligent, they will start reading and highlight stuff, but how do they choose what to highlight? How do they know which is a tree and which is the forest?

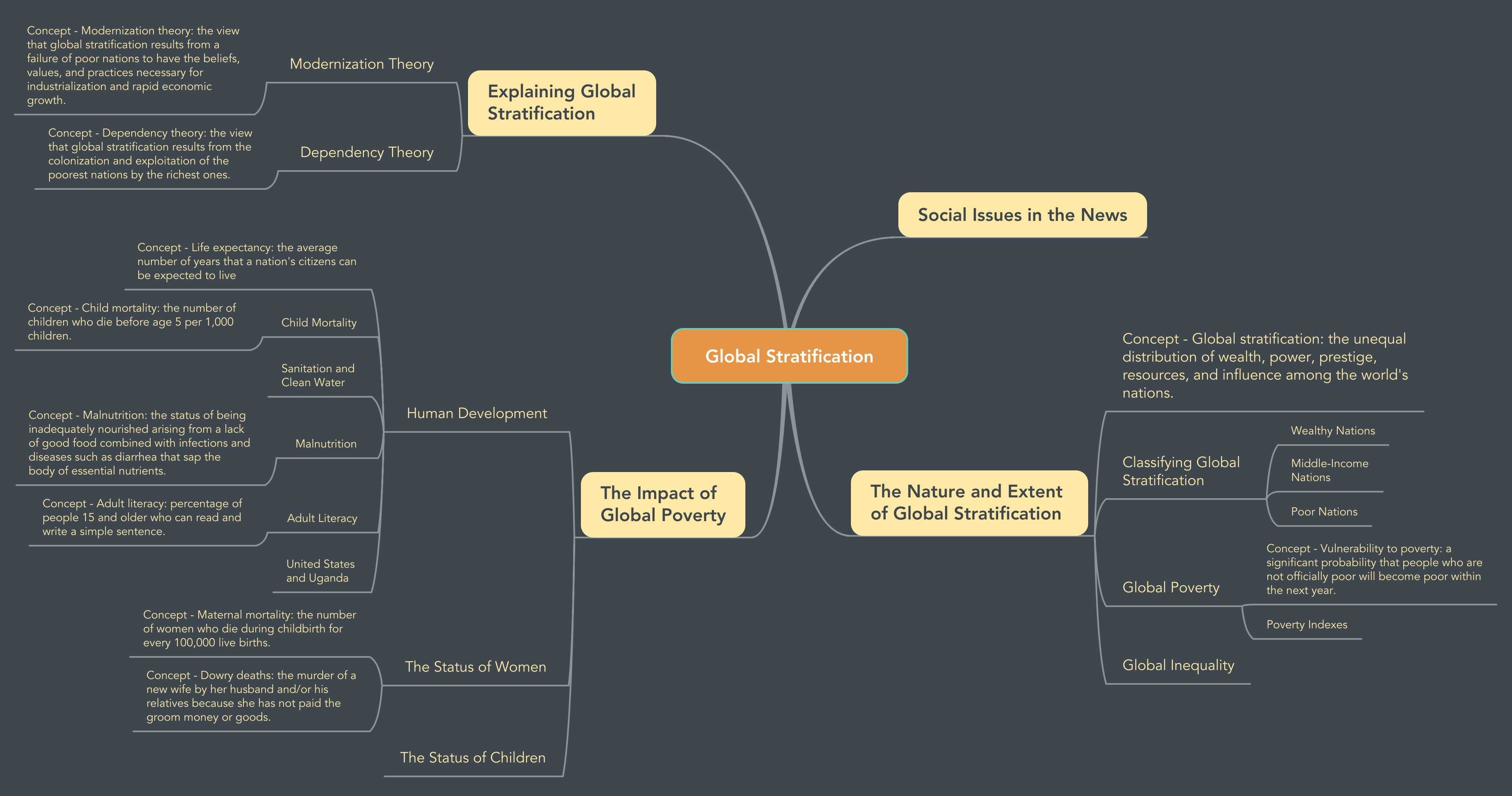

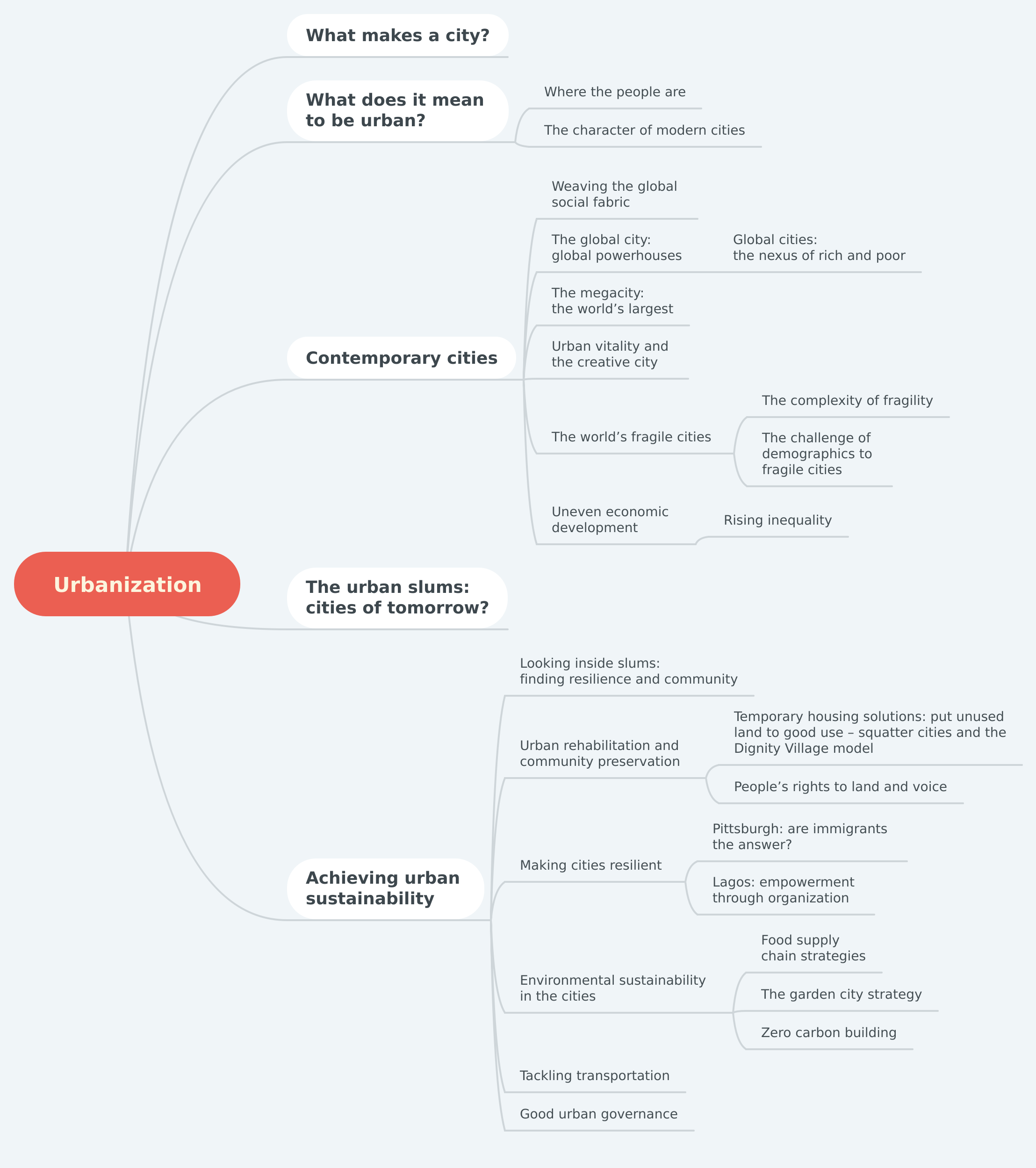

This is why I have started asking students to map the assigned textbook chapters outlines before they even read. I tell them to map without reading. First, map, then read. And specifically, depending on the texbook formatting, I will ask for an outline of the chapter (not the boxes, not the images, not the other content that is not part of the body of the text) or the outline of the chapter + the concepts with their definitions.

Doing so will give them the gist of what the chapter is about, its general organizations, which sub-sections are part of which larger sections (don’t assume your students know how to figure this out on their own) and where the concepts fit.

Here is an example from my introduction to sociology class (see this link for a “live” version of the map):

Here is an example from my social problems class (see this link for a “live” version of the map):

The idea is that, through mapping, students will get a sense of what this chapter is about, what the different parts are, and a general sense of the content. After mapping, they are ready to start reading the chapter. I do recommend that they read each section separately, and stop after each section and take a break. I tell them not to try to read an entire chapter chapter in one seating. I tell them to look at a section in their map, look at what they mapped, and then go read that section. Stop, take a break, play a game, text a friend, go on social media for a few minutes. Then look at the next section on your map, and repeat.

For face-to-face classes, I require the maps to be completed before class (and yes, I attach points) and brought to class so, at the very least, if students have not read the assigned chapters, they have mapped them and have a broad sense of what we talk about. We can review some of the content in class, They can also use their maps in group activities.

I like the idea of chapter mapping because it does not require a lot of thinking on the students’ part. The content is given to them (the chapter outline). They do not have to come up with their own content. But doing so helps them get comfortable with the mapping process itself. Once they are over the novelty of having to do this, the maps can be done relatively quickly (10 to 15 minutes depending on the length and complexity of the chapter).

At the beginning of the semester, I do share a “why I am making you do this” document with my students so they know I’m not doing this out of sadism.

I also share a series of brief videos I created on mind mapping for their review, and for which they can earn an Mind Mapper badge (created through the Achievement tool in Blackboard). In this series, I explain the ins and outs of mapping, how to create a map. I also provide a few software recommendations.

I should not though that I very strongly wish that Blackboard had a mind mapping module or tool because I would use the heck out of it… and you would too after reading this post!

Enjoy the videos.

In the second part of this post, I will explore mapping for actual content.

As always, thanks for reading.

Christine