Remember when metacognition was going to be the theme for the semester (year?) and we all got a free book (raise your hands, how many of you read it??)? And then the world pandemic hit and our priorities shifted to making to the end of the term on remote instruction. And now, after pushing Summer online, we’re looking at a still-very-uncertain Fall term.

Colleagues, I would like to gently suggest that metacognition is more important now that we are pushing, by necessity, our students into delivery modes that they might not have chosen if face-to-face was an option.

Hence this book: Why Students Resist Learning – A Practical Model for Understanding and Helping Students (COD Library e-book link).

Students resistance to learning is one of those things where “you know it when you see it”. The book actually provides a definition:

“Student resistance is an outcome, a motivational state in which students reject learning opportunities due to systemic factors. The presence of resistance signals to the instructor the need to assess the systemic variables that are contributing to this outcome in order to intervene effectively and enhance student learning.”

(Loc. 301, Kindle edition)

Moreover,

“student resistance is the outcome or result of a confluence of forces, including institutional context, faculty attitudes and behaviors, faculty reactions to student behaviors, and powerful forces that drive and shape student expectations and reactions.

(Kindle Locations 275-277)

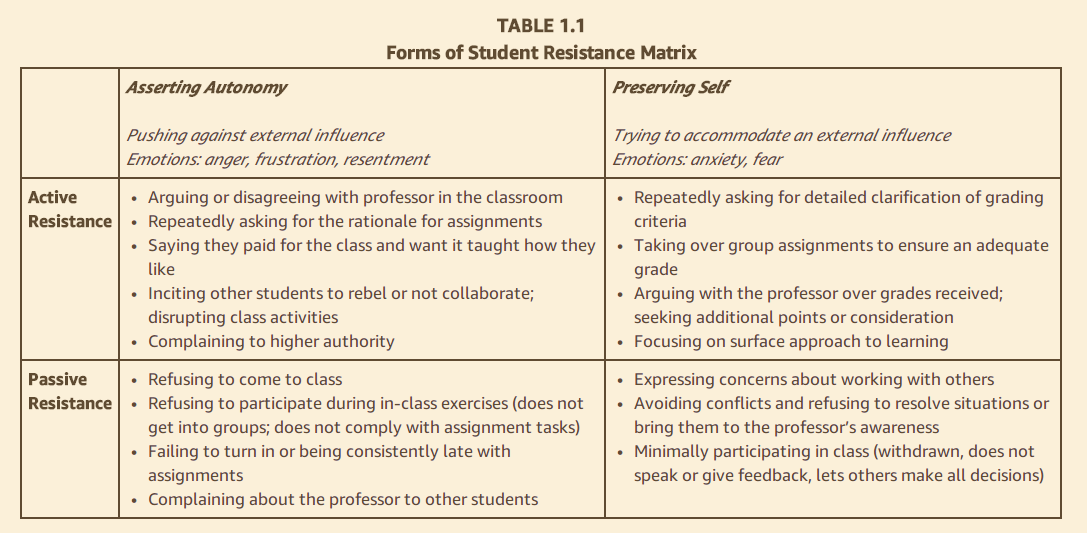

The authors further delineates student resistance based on two key motivations: assertion of autonomy and preservation of the self. They also articulate two broad types of resistance: passive and active. Based on those, they construct what they call a matrix of student resistance, which looks like this:

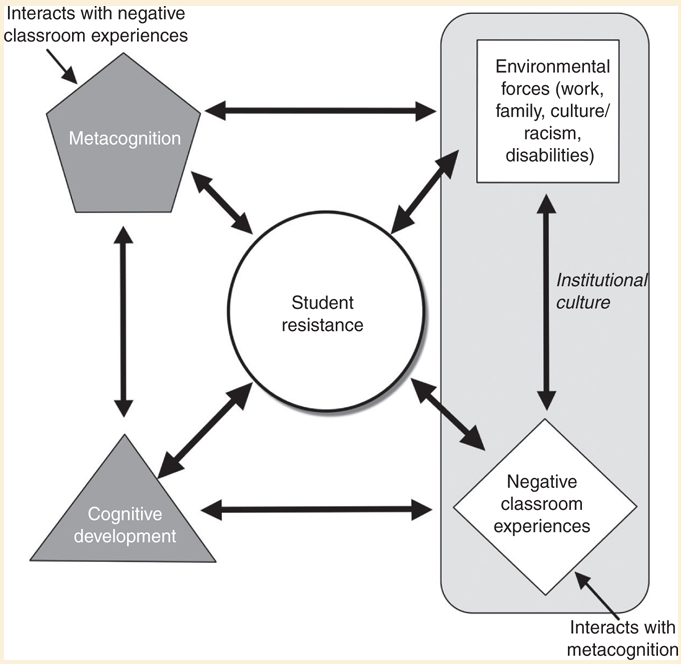

And based on that and other research on student resistance, the authors then articulate an Integrated Model of Student Resistance (bad graphic alert):

The model is presented and discussed in the early chapters of the book. The bulk of it, though, is dedicated to going through the elements of the model above but also offers strategies to push back on the elements of the model that trigger resistance.

One the key points that the authors make is that students are especially likely to engage in resistance to learning when faced with active learning or deep learning. And so, instructors who try to engage in such pedagogy should expect they’ll receive more resistance, and lower ratings on evaluation or on the site-that-shall-not-be-named.

The discussion of institutional factors focuses mostly on research universities, more than institutions like ours. However, we may ask ourselves whether or how our own institutional culture may contribute or reduce student resistance. The book does go into how institutions may (consciously or not) treat students as consumers, for instance.

When it comes to the environmental forces mentioned in the model, they refer to a lot of what Jenn Kelley has been doing with professional development and that the authors describe as equity pedagogy.

The authors also mention both sides of the faculty – student equation. Both students expectations and negative classroom experiences contribute to student resistance. One type of student expectations is what the authors call academic entitlement:

Students’ minds are not tabulae rasae; students bring with them ingrained expectations and attitudes that promote or harm active learning. One source of these resistant behaviors is academic entitlement, the tendency of an individual to expect academic success without a sense of personal responsibility for achieving that success

(Kindle Locations 2493-2495)

But on the faculty side:

Instructors enable academic entitlement by reneging on established course policies like assignment requirements and due dates, as well as offering excessive extra credit for missed deadlines or poor performance on assignments or tests.

(Kindle Locations 2527-2529)

This is also where a consumerist attitude can also enable students resistance, and the authors see student evaluations as part of such a consumerist mindset. They are actually quite scathing about the way students evaluations of teaching are generally administered in part because they foster such an attitude.

We already know that students also often adopt a fixed mindset (the idea that abilities are set once and for all and if you don’t have ability for X subject, then, you’ll never learn it) as opposed to a growth mindset. In addition, the authors suggest that students who lack self-efficacy (students’ perception of their ability to succeed, both socially and academically) are more likely to engage in passive resistance, and that underrepresented students are especially likely to lack in self-efficacy.

And there is a whole chapter on negative classroom experiences, which is the part where faculty have the most responsibility. So, the book is an invitation to reflect on our practice, face-to-face, virtually, online, and in hybrids.

And to circle back to the beginning of this post, you can see that metacognition is part of the model. What does this have to do with resistance?

The goal of promoting metacognition is to increase students’ responsibility for their own learning and to encourage them to become more active in the learning process (Flavell, 1979).

(Kindle Locations 3723-3724)

And that goal can be partially achieved by raising students awareness of their own mindset (fixed v. growth), and usual learning and studying strategies. The authors mention a whole of inventory questionnaires to get students thinking about their learning. The most famous one is the The Learning and Study Strategies Inventory (LASSI). Students can take it at COD (see here and check out all the tools available). Another one is the Study Process Questionnaire (SPQ). I’m attaching a version below so you can see what it’s looks like:

The authors recommend that if instructors do use those inventories or tools, then they should also have discussions in class on why they are important and why students should reflect on their study practices along with best practices and study strategies (we know there is a mismatch there).

I would also like to recommend taking a serious look at this website that offers lots of strategies to bring metacognition to class.

So, I really recommend this book (I have a few gripes here and there but they are minor). I also think that in the mess created by the pandemic, and our massive move to remote then to online, we should not forget the importance of metacognition. But as always, I would also recommend starting small and purposeful.

Thanks for reading.

Christine